Hortense Hueber, my mother

November 16, 2020 was the fiftieth anniversary of my mother's death. I sent a few photos of her to my friends and family members. They wanted to know more about her...

somebody you never knew...

She, was sent to a labor camp in the North of Bavaria, in Franconia, at Floss bei Weiden, near the Czech border, adjoining the concentration camp of Flossenbürg.

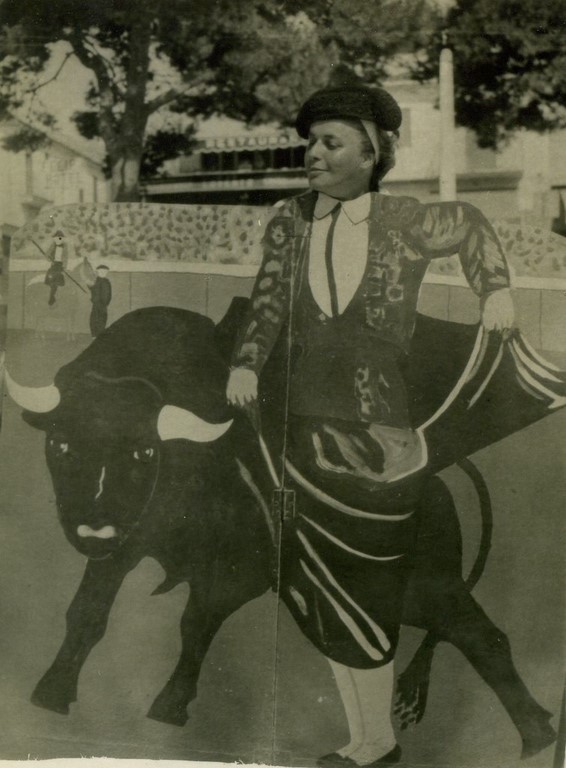

Majorca, 1961

Her brush with history

French friends have asked me if I knew more about the death, on December 27, 1944 of Colonel Fabien, who has to his name a metro-station and a square in Paris, the location of Oscar Niemeyer's landmark building of the headquarters of the Communist Party (a building which Al liked a lot...).

I know nothing more about Colonel Fabien, but I know this about Commandant Duval, who was also there, with his lady-friend Capitaine Maggie. Duval shot a hare in the Hardt Forest, which was then the front-line, and he brought it to my grandmother, who made it into a Hasenpfeffer. My grandparents' house was 800 meters away from the edge of the forest. They were all sitting there eating the hasenpfeffer - my grandfather, my grandmother, Duval, Maggie, my mother, François Horovitz - when the town-hall blew up (about 500m away) killing Colonel Fabien and six others and injuring dozens. Had it not been for the hasenpfeffer, Duval, Maggie and François might well have been at the town hall, where there was a canteen. (Never pass up a chance at Alsatian gastronomy...)

Duval and Maggie came to visit us after the war, when I was a little girl. I remember them well, the occasion was very cheerful. Duval was wearing a brown suit, Maggie a "tailleur" with a fitted waist. She had beautiful curly hair, which she had let my grandfather manually de-lice during the war - how could he ever forget! I also remember my grandfather telling me that whenever Commandant Duval was at the house, there would be two Senegalese bodyguards with machine guns standing guard before the door. When you wanted to go out, they crossed their weapons to bar the way. There was also a Senegalese with a machine-gun guarding the outhouse. This is what has come down to me.

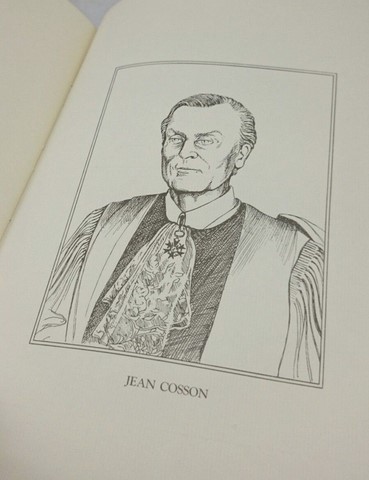

Until yesterday morning, when I did some research on the Net trying to find something on Commandant Duval, which at first did not look promising. But I got him. He was the sector chief for the Forces Françaises de l'Intérieur FFI (partisans) for Briey, in Meurthe- et-Moselle, in Lorraine, north of Metz, and I found a whole chapter about their activities in a book by Pierre Préval, quickly downloaded from amazon, aptly named Sabotage et Guérilla. After France had been liberated, except for Alsace, he joined up with Colonel Fabien and came to Habsheim. Duval was his combat name, his real name, I discovered, was Jean Cosson and he was a judge in Briey. He ended up a counsellor at the Cour de Cassation in Paris, the highest judiciary instance in France. (8.3.1916-3.12.1993). His picture, below, is from his book Les Industriels de la Fraude Fiscale.

At the same time, also in Meurthe-et-Moselle, a little bit south of Cosson-Duval's home turf, at Hériménil, near Lunéville, south of Nancy, was staying Al (my husband, Alfred de Grazia). He was there when, four days after the townhall in Habsheim blew up, December 31, he and some tens of thousands of others were rudely put on the road in the middle of the night in a snowstorm by the German attack Nordwind, in the aftermath of the Offensive des Ardennes (Battle of the Bulge).

answer to a friend

Dear G.,

You know, after fifty years, the pain is gone, and the sadness - almost. I was grasping at this straw to have a pretext for "outing" her to my friends and loved ones, who never knew her... She raised me alone. In a way, we lived together as a "couple..." Strange to say, by her character and temperament, she resembled Al. I married my mother. (And he, with me, married his father, as he told me...)

I love the picture from Spain. It was taken by a photographer with an old wooden camera, who had set up folding screens in a village square in Majorca. I am absolutely certain that Al would have rushed to have his picture taken as a toreador, exactly like she did... For those who expressed interest, I made a little bio. But there is so much more to say about her...

By the way, her Jewish Hungarian-French lover’s name was François Horovitz and James Salter’s “real” name was James Horowitz... get it?

I am sorry to hear of your friend. She died of breast cancer. She told nobody about her cancer. I was the only one to know, for five years, between ages 17 and 22. She died on the eve of my 22nd birthday. Not that her death struck me down. Before I was 24, my first novel was published by one of the big French publishers, and I got a prize from the Académie Française and the medal of honor of my birth city of Mulhouse - of which I shall always be proud. But I always resented the burden that her cancer and her silence put onto me. The terrible thing with degenerative diseases, like cancer, and Alzheimer, and Parkinson’s etc. is that they spoil one’s memory of the deceased... it takes about fifty years to get over it, and few live long enough...

She died on the eve of my 22nd birthday. Believe it or not, she told me then: “Go, you are a child of luck...” meaning, that I was lucky to be so free at such a young age... She had read a lot of psychoanalytic literature. She did not have her "Certificat d'Etudes" but through me, as years passed, she read Dostoïevski, and Proust, and Joyce... Ulysses was familiar territory for her: she had had the same job in Mulhouse as Leopold Bloom had in Dublin: canevassing the city for advertisements. When she died, she was reading Günther Grass' Tin Drum. She didn't get to the end of it.

Today, I am turning 72. Here’s a picture of my breakfast. With champagne. She always, even as a little child, celebrated my birthday with champagne. And of course, I continued with Al. Marco once told me that champagne is the only wine you can drink for breakfast because it's not destroyed by coffee. I poured four flutes, for me, Al, Vladimir and her. And I drank for all four of them. You think that I am crazy? Of course I am! And a bit drunk, too... At every meal, I am facing the portrait of Anna Maria, Marco’s mother...

At 12:15, Florence brought me a little cake... so sweet of her...

I ate almost all of it. I didn’t blow out the candle, I let it go out by itself, feeding it with my breath... it seemed to go on forever, but then it went up in smoke, and that was it...

Guess what my blood pressure was this morning, doc? 124/66 with 80 ticks... Looks like I am not quite done yet...

Love, as always,

A.

Basel, 1965